2008 indo-caribbean women's empowerment Summit

Towards Empowerment

by Sasha K. Parmasad

Printed in the Caribbean New Yorker

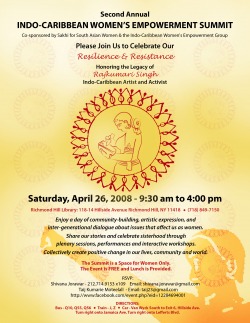

What does it mean to be an Indian-Caribbean woman, your body full of history, full of memory, a bridge spanning the kala-pani, stretching across time and space, from India to the Caribbean to North America, asserting: These hands have torn down forests, have taught drums how to speak, have built civilizations with cutlass, shovel, belna and pen. What does it mean to be an Indian-Caribbean woman? On the 26th of April, 2008 the second annual Indo-Caribbean Women’s Empowerment Summit, co-sponsored by Sakhi and the Indo-Caribbean Women’s Empowerment Group, was held at the Richmond Hill Library. The event, spearheaded by Taij Kumarie Moteelall, Shivana Jorawar and Simone Jhingoor, opened with a moment of silence in remembrance of Natasha Ramen and Guiatree Hardat: young Indo-Caribbean women, victims of abuse, who were brutally killed last year. At this year’s summit four generations of Indo-Caribbean women from Guyana, Suriname, Jamaica and Trinidad came together to share their stories of resilience, engage in dialogue about the issues most affecting them, and determine what steps could be taken to break the silence surrounding destructive cycles of domestic violence. Through the vibrant, inter-generational dialogue that characterized the day, it became evident to participants that being an Indo-Caribbean woman meant embracing the legacy of strength and resistance bequeathed to them by their indentured grandmothers, their mothers, their women sugar-workers, home-makers, activists, artists, writers – Mahadai Das, Lady Naidoo, Rajkumari Singh (to name a few). Last year’s summit honored the sugarcane worker and political organizer, Kowsilla (aka Alice), who fought to uplift the condition of the poor and oppressed in Guyana. She became a martyr in 1964 when an estate scab drove a tractor through her, severing her body in two.

This year’s summit paid tribute to the pioneering, intrepid Guyanese writer, political activist, educator and cultural leader, Rajkumari Singh. Her life’s work was motivated by a profound respect for her cultural heritage and an enduring love for her country. These concerns are demonstrated in her poem, Per-Ajie: “Per Ajie/ Somewhere ‘neath/ Guyana’s skies/ In Guyana’s soil/ Two blades you caused/ To grow where first/ ‘Twas/ But only one.” The poem, powerfully dramatized at the summit by Rajkumari’s daughter, Pritha Singh, had been written as a tribute to Guyana’s first indentured woman who is symbolized by the generic term, Ajie: grandmother. Interestingly, the lines quoted above beautifully capture the legacy left to the world by Rajkumari herself. Through her nurturing of younger generations of Caribbean writers and artists, many blades she caused to grow where first there were but a few. In a manner, this growing of many blades also speaks to the central goal of the summit: to facilitate the empowerment of many more Indo-Caribbean women. Through the honoring of women ancestors, through honest dialogue about domestic abuse, the summit suggested to the women present that being an Indo-Caribbean woman meant building on their rich inheritance of struggle in order to uplift themselves, their community, and the wider society.

For more than one hundred and sixty years the history of Indians in Trinidad, Guyana, Jamaica and other parts of the Caribbean has been marginalized and often misrepresented. Indian children growing up both within Caribbean and North American contexts learn only a smattering (if anything) about the indentureship system that brought their ancestors to toil as unfree labourers on sugarcane plantations in the Caribbean. They learn only a smattering about the painstaking labor and wondrous determination with which their ancestors reconstituted, from fragments of memory and practice, a new civilization in Caribbean landscapes long plundered by colonial conquest. Without a knowledge of one’s history, of where one comes from, without a knowledge of self, how can one move boldly forward in the world? As elders often say: Yuh must know where yuh come from, to know where yuh going. Recognizing this, coordinators of the summit, in an effort to build self-knowledge and empower women, organized workshops and group activities that fostered inter-generational sharing and teaching. In one such activity each woman was asked to select a label printed with a particular message – for example: Mind you mouth; Don’t let any man run you; Don’t let anyone talk your name – and then discuss with the person sitting next to her what had motivated her to choose it. As women in their eighties conversed with women in their thirties, as those in their fifties conversed with teenagers, myriad stories unfolded stretching from the 1920s in the Caribbean, through riots and social upheavals, marriages and births, divorces and migrations, right up to 2008 in Richmond Hill, New York.

A timeline of Indo-Caribbean history in Guyana, Trinidad and the United States (a work in progress) was also constructed and women, on entering the Library, were asked to review it, jot down and date an event of deep personal significance, and insert this into the timeline. Through this exercise women were encouraged to “voice”, to insert their concrete presence into larger historical narratives (the product of colonial, patriarchal systems) in which their stories have been traditionally marginalized, their role as the makers of history, mostly overlooked. This “disentombment” of the Indo-Caribbean woman – her strivings, preoccupations, strengths, achievements, trials, methods of resisting varied forms of oppression – was at the heart of the events that unfolded at the Richmond Hill Library. It was a “disentombment” not only of the past, but also of the present, of the very women who attended the summit. For example, the sprightly, articulate Muslim-Guyanese woman in her eighties who, seeing an advertisement for the summit in the newspaper had, on her own, boarded the Q10 bus to attend. The mothers who had journeyed on their own from the Caribbean to the United States to carve a new life for their families; their daughters who had grown up in Richmond Hill and the Bronx, whom they had not wanted to attend a college that would require them to leave home; Christian, Muslim, and Hindu women who brought some to tears with their stories of different types of domestic abuse; women in their fifties whose parents had insisted that they “take their education” and others whose parents had taken them out of school as they had grown older. An outspoken mother who had cleaned houses in the Bronx in order to bring her family to the United States and then, at thirty-eight, had entered college determined to obtain her BA, after which she had gone on to obtain her Master’s Degree. “Disentombment” was recognized as a necessary step on the road towards empowerment.

As the stories and experiences of these women were “disentombed” what was strikingly evident was the degree to which the older generation of women who had grown up in the Caribbean and migrated to America late in life – grandmothers, mothers – had been bold pioneers: creators and shapers of culture, community and history in this new context, not passive recipients, as is so often thought. It also became evident that Indo-Caribbean women of each of the four generations present had, in their own way, taken conscious, courageous decisions to resist patriarchy and positively redefine their familial roles as mother, daughter, wife. In many cases they had done this against the expressed wishes of parents, in-laws and husbands, and had sometimes been violently reprimanded and socially stigmatized as a consequence of their resistance. However, in quite a few cases their redefinition of these roles had been actively supported and encouraged by parents and husbands. This led some women to suggest that to bring about change within the community, similar educational, empowerment workshops would have to be organized for Indo-Caribbean men. Indeed, in one exercise when women were asked to contemplate what kind of persons they would be in a world in which patriarchy was reversed – all positions of leadership and power held by women – a few indicated that, instead of attending a summit for the empowerment of women, they would be attending one for the empowerment of men. It was their wish to build a community, a world, in which there was a balance of power between the sexes, in which heinous inequalities and abuses would not have a place.

As the summit drew to a close participants were asked to take a few minutes to reflect on what they had learnt and determine how they could take action in their daily lives to break cycles of abuse and the silence surrounding the issue of domestic violence. They were encouraged to share the information and resources they had gathered at the summit among other women. In a final act of solidarity women stood in a circle, fists striking air, and boldly chanted, “Warrior woman, raise your fist up high, liberation is a state of mind!” It became evident that the young Indo-Caribbean women who had organized the summit, while taking on the challenge of carving a new path for the community in this society, were following in the footsteps of mothers and grandmothers – jahaajee behins – who had done the same for their own generations. Jahaajee behin, meaning boat-sister, was the term used by Hindu, Muslim and Christian indentured labourers to refer to shipmates with whom they had withstood the hazardous voyage from India to Trinidad. These ties, born out of common struggle and resistance, were said to be as close as ties of blood. On the 26th of April, at the Richmond Hill Library, the women came together as jahaajee behins. It became abundantly clear that the young organizers of the summit, in fact, belonged to a tradition of revolutionary women.

by Sasha K. Parmasad

Printed in the Caribbean New Yorker

What does it mean to be an Indian-Caribbean woman, your body full of history, full of memory, a bridge spanning the kala-pani, stretching across time and space, from India to the Caribbean to North America, asserting: These hands have torn down forests, have taught drums how to speak, have built civilizations with cutlass, shovel, belna and pen. What does it mean to be an Indian-Caribbean woman? On the 26th of April, 2008 the second annual Indo-Caribbean Women’s Empowerment Summit, co-sponsored by Sakhi and the Indo-Caribbean Women’s Empowerment Group, was held at the Richmond Hill Library. The event, spearheaded by Taij Kumarie Moteelall, Shivana Jorawar and Simone Jhingoor, opened with a moment of silence in remembrance of Natasha Ramen and Guiatree Hardat: young Indo-Caribbean women, victims of abuse, who were brutally killed last year. At this year’s summit four generations of Indo-Caribbean women from Guyana, Suriname, Jamaica and Trinidad came together to share their stories of resilience, engage in dialogue about the issues most affecting them, and determine what steps could be taken to break the silence surrounding destructive cycles of domestic violence. Through the vibrant, inter-generational dialogue that characterized the day, it became evident to participants that being an Indo-Caribbean woman meant embracing the legacy of strength and resistance bequeathed to them by their indentured grandmothers, their mothers, their women sugar-workers, home-makers, activists, artists, writers – Mahadai Das, Lady Naidoo, Rajkumari Singh (to name a few). Last year’s summit honored the sugarcane worker and political organizer, Kowsilla (aka Alice), who fought to uplift the condition of the poor and oppressed in Guyana. She became a martyr in 1964 when an estate scab drove a tractor through her, severing her body in two.

This year’s summit paid tribute to the pioneering, intrepid Guyanese writer, political activist, educator and cultural leader, Rajkumari Singh. Her life’s work was motivated by a profound respect for her cultural heritage and an enduring love for her country. These concerns are demonstrated in her poem, Per-Ajie: “Per Ajie/ Somewhere ‘neath/ Guyana’s skies/ In Guyana’s soil/ Two blades you caused/ To grow where first/ ‘Twas/ But only one.” The poem, powerfully dramatized at the summit by Rajkumari’s daughter, Pritha Singh, had been written as a tribute to Guyana’s first indentured woman who is symbolized by the generic term, Ajie: grandmother. Interestingly, the lines quoted above beautifully capture the legacy left to the world by Rajkumari herself. Through her nurturing of younger generations of Caribbean writers and artists, many blades she caused to grow where first there were but a few. In a manner, this growing of many blades also speaks to the central goal of the summit: to facilitate the empowerment of many more Indo-Caribbean women. Through the honoring of women ancestors, through honest dialogue about domestic abuse, the summit suggested to the women present that being an Indo-Caribbean woman meant building on their rich inheritance of struggle in order to uplift themselves, their community, and the wider society.

For more than one hundred and sixty years the history of Indians in Trinidad, Guyana, Jamaica and other parts of the Caribbean has been marginalized and often misrepresented. Indian children growing up both within Caribbean and North American contexts learn only a smattering (if anything) about the indentureship system that brought their ancestors to toil as unfree labourers on sugarcane plantations in the Caribbean. They learn only a smattering about the painstaking labor and wondrous determination with which their ancestors reconstituted, from fragments of memory and practice, a new civilization in Caribbean landscapes long plundered by colonial conquest. Without a knowledge of one’s history, of where one comes from, without a knowledge of self, how can one move boldly forward in the world? As elders often say: Yuh must know where yuh come from, to know where yuh going. Recognizing this, coordinators of the summit, in an effort to build self-knowledge and empower women, organized workshops and group activities that fostered inter-generational sharing and teaching. In one such activity each woman was asked to select a label printed with a particular message – for example: Mind you mouth; Don’t let any man run you; Don’t let anyone talk your name – and then discuss with the person sitting next to her what had motivated her to choose it. As women in their eighties conversed with women in their thirties, as those in their fifties conversed with teenagers, myriad stories unfolded stretching from the 1920s in the Caribbean, through riots and social upheavals, marriages and births, divorces and migrations, right up to 2008 in Richmond Hill, New York.

A timeline of Indo-Caribbean history in Guyana, Trinidad and the United States (a work in progress) was also constructed and women, on entering the Library, were asked to review it, jot down and date an event of deep personal significance, and insert this into the timeline. Through this exercise women were encouraged to “voice”, to insert their concrete presence into larger historical narratives (the product of colonial, patriarchal systems) in which their stories have been traditionally marginalized, their role as the makers of history, mostly overlooked. This “disentombment” of the Indo-Caribbean woman – her strivings, preoccupations, strengths, achievements, trials, methods of resisting varied forms of oppression – was at the heart of the events that unfolded at the Richmond Hill Library. It was a “disentombment” not only of the past, but also of the present, of the very women who attended the summit. For example, the sprightly, articulate Muslim-Guyanese woman in her eighties who, seeing an advertisement for the summit in the newspaper had, on her own, boarded the Q10 bus to attend. The mothers who had journeyed on their own from the Caribbean to the United States to carve a new life for their families; their daughters who had grown up in Richmond Hill and the Bronx, whom they had not wanted to attend a college that would require them to leave home; Christian, Muslim, and Hindu women who brought some to tears with their stories of different types of domestic abuse; women in their fifties whose parents had insisted that they “take their education” and others whose parents had taken them out of school as they had grown older. An outspoken mother who had cleaned houses in the Bronx in order to bring her family to the United States and then, at thirty-eight, had entered college determined to obtain her BA, after which she had gone on to obtain her Master’s Degree. “Disentombment” was recognized as a necessary step on the road towards empowerment.

As the stories and experiences of these women were “disentombed” what was strikingly evident was the degree to which the older generation of women who had grown up in the Caribbean and migrated to America late in life – grandmothers, mothers – had been bold pioneers: creators and shapers of culture, community and history in this new context, not passive recipients, as is so often thought. It also became evident that Indo-Caribbean women of each of the four generations present had, in their own way, taken conscious, courageous decisions to resist patriarchy and positively redefine their familial roles as mother, daughter, wife. In many cases they had done this against the expressed wishes of parents, in-laws and husbands, and had sometimes been violently reprimanded and socially stigmatized as a consequence of their resistance. However, in quite a few cases their redefinition of these roles had been actively supported and encouraged by parents and husbands. This led some women to suggest that to bring about change within the community, similar educational, empowerment workshops would have to be organized for Indo-Caribbean men. Indeed, in one exercise when women were asked to contemplate what kind of persons they would be in a world in which patriarchy was reversed – all positions of leadership and power held by women – a few indicated that, instead of attending a summit for the empowerment of women, they would be attending one for the empowerment of men. It was their wish to build a community, a world, in which there was a balance of power between the sexes, in which heinous inequalities and abuses would not have a place.

As the summit drew to a close participants were asked to take a few minutes to reflect on what they had learnt and determine how they could take action in their daily lives to break cycles of abuse and the silence surrounding the issue of domestic violence. They were encouraged to share the information and resources they had gathered at the summit among other women. In a final act of solidarity women stood in a circle, fists striking air, and boldly chanted, “Warrior woman, raise your fist up high, liberation is a state of mind!” It became evident that the young Indo-Caribbean women who had organized the summit, while taking on the challenge of carving a new path for the community in this society, were following in the footsteps of mothers and grandmothers – jahaajee behins – who had done the same for their own generations. Jahaajee behin, meaning boat-sister, was the term used by Hindu, Muslim and Christian indentured labourers to refer to shipmates with whom they had withstood the hazardous voyage from India to Trinidad. These ties, born out of common struggle and resistance, were said to be as close as ties of blood. On the 26th of April, at the Richmond Hill Library, the women came together as jahaajee behins. It became abundantly clear that the young organizers of the summit, in fact, belonged to a tradition of revolutionary women.