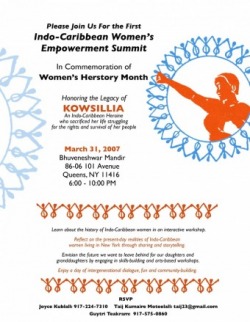

2007 Indo-Caribbean Women's Empowerment Summit

Breaking the Silence

Written by Shivana Jorawar,

(Published in the Caribbean New Yorker)

Imagine four generations of Indo-Caribbean women openly discussing domestic violence, women’s leadership and the role of cultural practices in silencing women. Imagine us searching our souls for ways to empower ourselves and spawn broad-based empowerment among women in our community. Can you even conceive of it?

On March 31st, 2007, this is exactly what took place. In the wake of Natasha Ramen’s brutal murder by her alleged rapist, a group of concerned women broke the silence around gender inequity in the Indo-Caribbean community.

At the 2007 Indo-Caribbean Women’s Empowerment Summit, the walls of the Bhuvaneshwar Mandir in Queens heard emotional stories of abuse and expressions of determination to stand up for our rights and end violence against women. Outraged by the Ramen case, community leaders Gayatri Teakram, Taij Kumarie Moteelall, Simone Jhingoor, and Vijai Kublall organized the event in hopes of creating a safe space for women in our community to build collective power and bring our voices to the forefront on issues concerning our safety and overall wellbeing.

When asked to raise our hands if we, or someone we know, had been abused, every one of the 30 women present raised our hands high. In a 2006 survey of 131 Richmond Hill residents done by Sakhi for South Asian Women, 50 respondents said they or someone they know has experienced domestic violence. An additional 13 respondents said they were “not sure” and 7 declined to answer. If violence against women in the Indo-Caribbean community is a problem, why then do we neglect to address it publicly? More broadly, why has there until now been no significant dialogue around women’s issues?

At the summit, women agreed that social stigma plays a big role in preventing victims of violence from coming forward and in preventing discussion of women’s issues in general. Our community and traditions demand that women be “chaste,” and broken marriages are still considered taboo. These two stigmas leave women with very few options to transform or escape abusive situations, forcing them to remain tight-lipped and endure their pain. Oftentimes women are enduring pain for the sake of their children. However, what we discovered is that we are simply perpetuating violence and bringing greater pain to our children who will grow up to replicate the behaviors that were modeled for them.

Some women present also brought up the impact of immigration status on a victim’s willingness to come forward. Often, abusers will threaten to withhold citizenship papers from a woman if she exposes him. Undocumented women may also be uncomfortable approaching the police for help because of the misconception that they can be reported to the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

In light of the Ramen case, Gayatri Teakram emphasized that women may decline to come forward about their abuse because of the fear of continued or greater physical harm.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the summit was Taij Kumarie Moteelall’s presentation on the ways in which some religious scriptures have been misinterpreted to favor a patriarchal system. Citing the Manava Dharma Shastra or the “Laws of Manu,” Moteelall explained that texts written by men in ruling positions have become law and have shaped our cultural practices. For instance, one excerpt from the Manava Dharma Shastra reads, “In childhood a female must be subject to her father, in youth to her husband, when her lord is dead to her sons; a woman must never be independent.”

Breakout groups were charged with developing a 20-year vision for a transformed society and strategies to get there. The group focused on cultural roots of oppression found that our religious institutions are a fertile place for healing and change. However, in order to make this a reality, the group suggested having a women’s group and/or a female spokesperson that can represent women and give voice to the issues challenging us. We also discussed reading our sacred texts, such as the Vedas, and gaining firsthand knowledge of our religion as a source of empowerment.

The energy of solidarity at this groundbreaking event was so strong that one woman commented she could feel our power before even stepping into the room. Several women celebrated the fact that they were able to break out of isolation and find solace in knowing that they were not alone in their struggles. “Strength in numbers” was a common theme of the reflection we all did at the end of the event.

All the women present expressed enthusiasm for taking the discussions we had further and organizing around empowering Indo-Caribbean women on a larger scale. Because of this overwhelming show of support, organizers of the event plan to expand the core planning team and to hold women’s empowerment meetings regularly [details to be announced at a later date]. We are confident that our numbers and movement will grow in the coming months and years, and that our community will look different as a result of our passion and dedication.

Written by Shivana Jorawar,

(Published in the Caribbean New Yorker)

Imagine four generations of Indo-Caribbean women openly discussing domestic violence, women’s leadership and the role of cultural practices in silencing women. Imagine us searching our souls for ways to empower ourselves and spawn broad-based empowerment among women in our community. Can you even conceive of it?

On March 31st, 2007, this is exactly what took place. In the wake of Natasha Ramen’s brutal murder by her alleged rapist, a group of concerned women broke the silence around gender inequity in the Indo-Caribbean community.

At the 2007 Indo-Caribbean Women’s Empowerment Summit, the walls of the Bhuvaneshwar Mandir in Queens heard emotional stories of abuse and expressions of determination to stand up for our rights and end violence against women. Outraged by the Ramen case, community leaders Gayatri Teakram, Taij Kumarie Moteelall, Simone Jhingoor, and Vijai Kublall organized the event in hopes of creating a safe space for women in our community to build collective power and bring our voices to the forefront on issues concerning our safety and overall wellbeing.

When asked to raise our hands if we, or someone we know, had been abused, every one of the 30 women present raised our hands high. In a 2006 survey of 131 Richmond Hill residents done by Sakhi for South Asian Women, 50 respondents said they or someone they know has experienced domestic violence. An additional 13 respondents said they were “not sure” and 7 declined to answer. If violence against women in the Indo-Caribbean community is a problem, why then do we neglect to address it publicly? More broadly, why has there until now been no significant dialogue around women’s issues?

At the summit, women agreed that social stigma plays a big role in preventing victims of violence from coming forward and in preventing discussion of women’s issues in general. Our community and traditions demand that women be “chaste,” and broken marriages are still considered taboo. These two stigmas leave women with very few options to transform or escape abusive situations, forcing them to remain tight-lipped and endure their pain. Oftentimes women are enduring pain for the sake of their children. However, what we discovered is that we are simply perpetuating violence and bringing greater pain to our children who will grow up to replicate the behaviors that were modeled for them.

Some women present also brought up the impact of immigration status on a victim’s willingness to come forward. Often, abusers will threaten to withhold citizenship papers from a woman if she exposes him. Undocumented women may also be uncomfortable approaching the police for help because of the misconception that they can be reported to the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

In light of the Ramen case, Gayatri Teakram emphasized that women may decline to come forward about their abuse because of the fear of continued or greater physical harm.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the summit was Taij Kumarie Moteelall’s presentation on the ways in which some religious scriptures have been misinterpreted to favor a patriarchal system. Citing the Manava Dharma Shastra or the “Laws of Manu,” Moteelall explained that texts written by men in ruling positions have become law and have shaped our cultural practices. For instance, one excerpt from the Manava Dharma Shastra reads, “In childhood a female must be subject to her father, in youth to her husband, when her lord is dead to her sons; a woman must never be independent.”

Breakout groups were charged with developing a 20-year vision for a transformed society and strategies to get there. The group focused on cultural roots of oppression found that our religious institutions are a fertile place for healing and change. However, in order to make this a reality, the group suggested having a women’s group and/or a female spokesperson that can represent women and give voice to the issues challenging us. We also discussed reading our sacred texts, such as the Vedas, and gaining firsthand knowledge of our religion as a source of empowerment.

The energy of solidarity at this groundbreaking event was so strong that one woman commented she could feel our power before even stepping into the room. Several women celebrated the fact that they were able to break out of isolation and find solace in knowing that they were not alone in their struggles. “Strength in numbers” was a common theme of the reflection we all did at the end of the event.

All the women present expressed enthusiasm for taking the discussions we had further and organizing around empowering Indo-Caribbean women on a larger scale. Because of this overwhelming show of support, organizers of the event plan to expand the core planning team and to hold women’s empowerment meetings regularly [details to be announced at a later date]. We are confident that our numbers and movement will grow in the coming months and years, and that our community will look different as a result of our passion and dedication.